Do 70% of transformations fail?

What evidence is there this is actually true?

This week’s ‘Caveat Emptor’ investigation probes the murky world of research into organisational transformation. Is it really true that ‘70% of organisational transformation efforts fail’?

The claim initially attracted the attention of our investigators because this tripped three separate alarms we apply when assessing ‘suspicious’ statistics.

Firstly, the research evidence behind this particular claim is rarely stated nor is essential contextual information provided. For example – what does ‘fail’ actually mean in organisational terms. Organisational collapse? Mass redundancies? Financial disaster? Mild inconvenience for users? A poor return on the investment originally projected? The claim is meaningless without understanding what criteria were applied.

Secondly, it seemed very unlikely that any genuinely evidence-based research study would result in a statistic that rounds precisely to 70 per cent, applicable in all conceivable circumstances!

Finally, this particular claim is made most vocally and insistently by vendors offering advice, products and services to organisations engaged in, or contemplating digital transformation. These vendors arguably have a compelling economic motive to promote such a claim. If transformation is demonstrably very challenging, then the need for third party support becomes more pressing and the budgets for mitigating risk correspondingly large!

Earlier today, Sam Rogers posted a positive review on LinkedIN concerning the audio version of the book by Tony Saldanha pictured above. We have yet to read what sounds like a very interesting book, but the blurb on Amazon immediately caught our attention:

The phrase in bold above leaps off the page and will probably be familiar to many working in the field of organisational transformation.

Similar claims have been made by a wide range of commentators. Take a look at this Google Search and you will see what we mean! This statistic certainly looks like a well-established fact, so why would anyone ever dream of questioning this?

On September 30th 2019 a ‘Customer Experience Futurist, Author and Keynote Speaker’ made a typically bold statement in the opening line of her Forbes article: ‘Companies That Failed At Digital Transformation And What We Can Learn From Them’:

As in other cases we explored, Morgan broadly attributes the evidence for this statistic with a link to a generic McKinsey webpage, but this does not contain any content of value to our investigators in substantiating the claim.

However we had a breakthrough when we unearthed a 2011 study in the Journal of Change Management, led by the University of Brighton researcher Mark Hughes.

The abstract explains that Hughes critically investigated five separate published instances identifying a 70 per cent organizational-change failure rate. In each instance, his review highlighted the absence of valid and reliable empirical evidence to support the espoused 70 per cent failure rate. Whilst the existence of this popular narrative was acknowledged, he found absolutely no valid and reliable empirical evidence to support the claim.

Please download the full report and read this for yourself!

As you will see, Hughes traces the mythical 70% failure rate back to the 1993 book ‘Reengineering the Corporation‘, in which authors Michael Hammer and James Champy stated:

From that point on, Hammer and Champy’s “unscientific estimate” took on a ‘wildfire’ life of its own.

A 1994 article in the peer-reviewed journal Information Systems Management presents Hammer and Champy’s estimate as a fact and changes “50 percent to 70 percent” to just “70 percent.”

In Hammer’s 1995 book, The Reengineering Revolution, he valiantly attempts to set the record straight:

There is no inherent success or failure rate for re-engineering.”

Sadly, despite Michael Hammer’s belated attempts at clarification, the 70 percent estimate has continued to be cited as fact right up to the present day. – It proved impossible to get the toothpaste back into the tube!

So where does McKinsey come back into this tangled story?

Well – according to this HBR article by Nick Tasler, back in 2008 McKinsey surveyed 1,546 executives. 38% of their respondents said “the transformation was ‘completely’ or ‘mostly’ successful at improving performance, compared with 30 percent similarly satisfied that it improved their organization’s health.”

It was clearly tempting for those wedded to the 70% narrative to claim that since only 30-38% of change initiatives are “completely/mostly successful,” then 62-70% must be failures.

However, we understand the McKinsey authors added that “around a third [of executives] declare that their organizations were ‘somewhat’ successful on both counts.”

In other words, a third of executives believed that their change initiatives were total successes and another third believed that their change initiatives were more successful than unsuccessful. Under a third therefore admitted to having been involved in a transformation that was ‘completely’ or ‘mostly’ unsuccessful.”

This clearly does not sustain the 70% failure narrative!

In summary, this weeks ‘Caveat Emptor’ investigation reveals no evidence to support the notion even half of organisational change efforts fail. If you see statements to the contrary being made please ask to see the supporting evidence. If none is provided please set the record straight. We are unlikely to get the toothpaste back into the tube but at least we can try to clean up the mess!

Out of the Woods!

Out of the Woods!

Why debate the effectiveness of different learning formats when all the reliable gains arise from improved efficiency?

Earlier today, someone I respect immensely reached out via LinkedIn mail to make the following comment about one of my LinkedIn Posts:

The irony was not lost on me. Learning professionals have spent too much of the last 30 years arguing fiercely about which method of learning is most effective!

Sadly, there is little validated peer-reviewed research to prove that any one method of learning is significantly more effective than another! Run a search for yourself on the DETA database and you will see what I mean!

Carrying out studies into relative effectiveness is really hard due to situational variations. Over many decades, the results of these studies indicate changing the medium of learning makes ‘no significant difference’ in terms of effectiveness. This leaves lots of scope for argument, but little scope for progress!

A little earlier today I received the following comment on the same LinkedIn post from another figure whom I also greatly respect:

That great comment essentially inspired me to write this blog post.

No-one would ever dispute that ‘learning by doing is a very effective learning strategy, ideally with a personal tutor to guide you, keep you safe.

The key challenge lies in offering ‘learning by doing’ at scale in a way that is economically competitive with other formats. Setting up the necessary supervision takes time and money, more resources are wasted due to errors, there is inevitably some risk. The list of issues goes on.

Virtual Reality learning may well have a part to play in relation to restoring a degree of competitiveness to ‘learning by doing’. However this is because simulating learning related assets, tools and environments improves efficiency and economy, not because the medium is inherently more effective than doing the real task in the real world.

In organisations, as in wider society, learning effectiveness is very rarely the sole consideration. Whilst it it is hard to prove that one learning format is significantly more effective than another – it is really easy to show that one format is much more efficient than another! This is where ‘learning by doing’ has traditionally struggled to compete.

The sweet-spot we are all seeking sits at a point-of-tension between learning efficiency and learning effectiveness. A place where the solution is effective and at the same time efficient enough to be economic and agile!

So why do does everyone obsess about learning effectiveness and talk so little about learning efficiency?

Into the woods!

Before formal learning developed all learning experiences were probably accidental and they involved ‘learning by doing’ at the pace of daily life. A situation that Plato and Roger Shank would heartily approve of!

Children got randomly lost in the woods and found that nettles sting the hard way. If they were lucky nothing worse occurred and they found their way home, having learned valuable lessons in local geography and botany. This was no doubt highly effective as a learning experience, but really inefficient and quite dangerous.

There are clear evolutionary benefits from recycling and sharing other people’s learning experiences. Anecdotes, old wives tales, folk and fairy tales were arguably designed to keep wayward children out of the woods or make them a little wiser if all else failed. More members of the next generation no doubt survived to adulthood as a result!

Modern education was built on the notion of learning acceleration. In other words, artificially accelerating the slow, unpredictable pace of individual learner experience. Rather than leaving things to chance, we design and assemble structured learner experiences, forming a constructive gradient that the learner can climb. We pack the learner experiences tightly into our accelerators, compressing them so that attitudes, knowledge and skills can be acquired in hours days, weeks or months rather than by chance over years or decades.

However, when learning became ‘an industry’ in the 20th Century, different commercial factions soon developed, each with investments in their own pet learning technology, format or medium. They were desperate to show that, irrespective of whatever concrete benefits their solution had to offer – theirs was more effective than one or more competitors. A long and sterile debate began!

The No Significant Difference database was first established in 2004 as a companion piece to Thomas L. Russell’s book, ‘The No Significant Difference Phenomenon’ (2001, IDECC, fifth edition). This was a fully indexed, comprehensive research bibliography of 355 research reports, summaries and papers that document no significant differences (NSD) in student outcomes between alternate modes of education delivery. The position on this has not changed markedly in the last 16 years!

Out of the woods!

Organisations have spent much of the last couple of decades stripping out the cost and inefficiencies previously associated with travelling to face-to-face courses. Remote, self-paced forms of digital learning are now the default choice of learning accelerator for many distributed organisations. A job well done!

However, we have now soaked up those efficiencies – so where next? Where and how will the next step-change in learning acceleration occur?

In a quest for increasing business agility employers find themselves driven to seek, adopt and implement innovative new forms of learning accelerator.

This is arguably where reliable future gains lie – not in squabbling over debatable gains in relative effectiveness but in seizing new efficiencies in learning acceleration.

We are all cooking up solutions but we are not out of the woods yet. I will highlight some of the most promising learning acceleration solutions in the coming weeks!

Moonrakers!

Moonrakers!

So the moon really is made of cream cheese?

Wiltshire once lay on the secret smuggling routes from the coast of England. Some local men had hidden contraband barrels of French brandy in a village pond. While trying to retrieve these with rakes at night, they were caught by the revenue men. However they explained by pointing to the moon’s reflection and saying they were trying to rake in the big round cheese. The revenue men, thinking they were simple yokels, laughed and went on their way. But, as the story goes, it was the Moonrakers who had the last laugh!

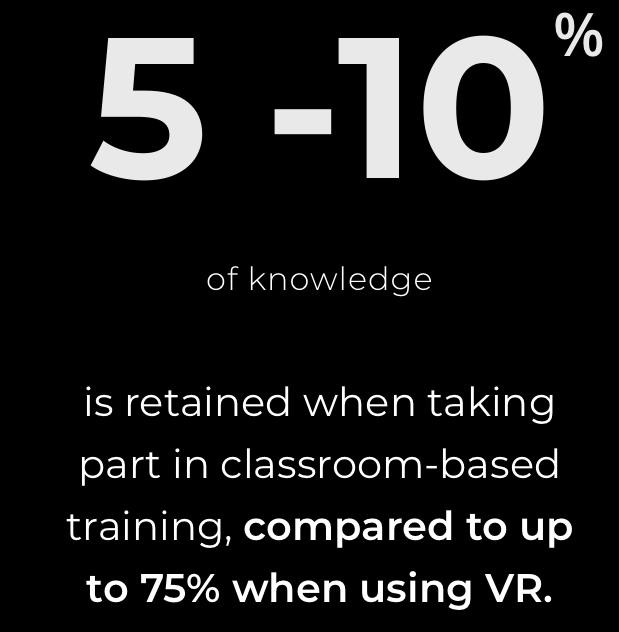

Over six months ago Learning Accelerators highlighted an extraordinary advertising claim on this website operated by a Virtual Reality learning company called ‘The Moonhub’, who claim to offer ‘a new frontier in training for forward-thinking companies’ Amongst other things the website carried the remarkable statement below:

Every business has to attract attention and we all have to earn a living, but this bold statement seemed a little outrageous, even by the loose standards of the Internet age.

Let’s reflect on that statement for a second. ‘5-10% of knowledge is retained in classroom-based training, compared to up to 75% when using VR’

We encourage buyers of learning solutions and services to apply their critical thinking skills. Is this advertising claim likely to be literally and scientifically true? And if it was – then how might scientists have proved this, given all of the variables involved?

If this statement is accurate then the social and economic implications would be huge. There are thousands of face-to-face training businesses across the UK and probably hundreds of thousands across the world. Beyond that, consider all the schools and universities across the globe offering various species of ‘classroom-based’ learning. The value-for-money provided by of all of these organisations is being denigrated equally in this one advertising claim.

The statement was not qualified in any way, nor was a source cited for these astonishing statistics. We lost no time in reaching out to the Founder/Director of The Moonhub Dami Hastrup, asking him to substantiate this specific advertising claim. This was his response:

Despite the offer to provide further information Mr Hastrup stopped answering questions via LinkedIn. We therefore looked more closely at the content of the VRLearn MASIE Report 2017 cited by The Moonhub, which confidently states:

Learning Accelerators has two concerns about the total reliance that The Moonhub is placing on this comment from Elliott Masie.

- Firstly, the statement by The Moonhub is unequivocal, unqualified by any reference to ‘a study’ – the information is presented as if it were a simple scientific rule!

- Secondly the rates of retention claimed and the ‘National Training Laboratory study’ form part of a notorious scientific myth commonly known as ‘Edgar Dale’s Cone of Experience’, depicted in one of its many manifestations below.

Edgar Dale (1900-1985) was an American educator best known for his ‘Cone of Experience’ and for his work on how to incorporate audio-visual materials into the classroom learning experience.

To illustrate the depth of bitter disrepute into which Dale’s ‘Cone’ has fallen in recent years, an entire issue of Educational Technology magazine (Volume LIV, Number 6- November-December 2014) was devoted to a page-by-page forensic destruction of this myth. We will leave it to Will Thalheimer to complete the demolition process with this ‘tour de force’ of research – Mythical Retention Data & The Corrupted Cone.

The National Training Laboratories (NTL) story is a subset of the same insidious myth. Images showing a pyramid like the one below have been circulating since the mid-1960’s. It is commonly alleged this pyramid was developed and used by NTL Institute at their Bethel, Maine campus in the early sixties when they were was still part of the National Education Association’s Adult Education Division.

As you can see, the Pyramid does imply lecture and reading results in average retention rates of under 10% and ‘Practice doing’ at 75%. This shape is the hazy reflection that the Moonrakers are pointing to on the surface of our pond. They are relying on this evidence to prove that face-to-face education is failing globally.

Let’s apply our critical thinking skills again. Run your eye further down towards the base of the pyramid. What do you see?

Audiovisual? Demonstration?, Discussion? Practice? – surely these are all sub-components in modern learning facilitation – in the classroom or elsewhere?

And how does the passage of time play into all this? Over what period do these retention periods apply?

As Will Thalheimer points out in his paper ‘How much do people forget?‘, sweeping rules-of-thumb that show people forgetting at some pre-defined rate are just plain false.

It now won’t come as a shock that the Pyramid has no verifiable scientific basis whatever!

Today, the NTL is known as the NTL Institute for Applied Behavioral Science. When approached with queries about the ‘Learning Pyramid’ they do acknowledge the attribution but explain they no any longer have – nor can they find, the original research that supports the numbers given above. They have attracted the ire of Will Thalheimer and many others as a result:

It remains unclear why Elliott Masie decided to highlight this long-lost NTL ‘research study’ in his VRLearn paper back in 2017, given that this had been publicly debunked in 2014. It is impossible to imagine why Elliott felt this discredited study (the content of which has been entirely lost) had any scientific relevance to readers interested in Virtual Reality in 2017.

Modern face-to-face learning facilitation is not comparable with lecturing formats already deemed ‘old-fashioned in the 1960’s. Since VR was unimaginable in the early 1960’s this medium was clearly not the benchmark that NTL researchers used for ‘Practice Doing’ – which is what Elliott describes as ‘the method of VR Learn.’

Six months ago The Moonhub was reminded that marketing communications by or from UK companies on their own websites are subject to regulation by the Advertising Standards Authority. The ASA will apply the UK Code of Non-broadcast Advertising and Direct & Promotional Marketing (CAP Code) to determine if advertising is essentially misleading.

However, the only material change in the position adopted by The Moonhub in the last six months occurred last week, when this link and the words ‘According to IVRTrain’ were inserted alongside other fresh citations as shown above.

On the basis of the facts outlined above Learning Accelerators has shown that the VRLearn document now publicly cited by The Moonhub does not provide adequate substantiation under Section 3.7 of the Non-Broadcast CAP, as follows:

3.7 – Before distributing or submitting a marketing communication for publication, marketers must hold documentary evidence to prove claims that consumers are likely to regard as objective and that are capable of objective substantiation. The ASA may regard claims as misleading in the absence of adequate substantiation

Learning Accelerators also believes that The Moonhub is breaching the following clauses of the Non-Broadcast CAP on exaggeration:

3.11 – “Marketing communications must not mislead consumers by exaggerating the capability or performance of a product.”

3.13 – “Marketing communications must not suggest that their claims are universally accepted if a significant division of informed or scientific opinion exists.”

Like the fabled Moonrakers of old, Dami Hastup and his colleagues at The Moonhub know full well what they are doing. They are simply pretending to be naiive to the truth because it suits them and presumably because some new clients are being drawn in by this claim.

The easiest thing to do in these circumstances is what the revenue men of old chose to do. Shrug our shoulders, have a chuckle and walk on, leaving the Moonrakers to go about their business!

But then again – that’s not really fair is it? Because in making this claim, month after month, The Moonhub is disparaging the value-for-money offered by thousands of hard-working face-to-face training and education businesses around the UK. Not only that, The Moonhub are also gaining an unfair competitive advantage over other immersive learning businesses too scrupulous to make this kind of sweeping statement.

Fortunately, if you’re a member of the public, you work for a competitor or are part of any group with an obvious interest, then you do have the right to complain to the Advertising Standards Authority about this under the CAP Code.

So if you feel strongly about this situation then we encourage you to submit a complaint via the Advertising Standards Authority website by clicking here.

Unless a line is drawn the Moonrakers will simply keep raking it in!

The Caveat Emptor campaign continues next week

RIA Window

"RIA Window" - a mystery thriller!

Does e-learning improve knowledge retention to 25-60% compared to 8-10% for face-to-face training? We investigate!

Have you ever read these words before? – “The Research Institute of America reports that learning retention rates improve from 8 to 10 percent for face-to-face training to 25 to 60 percent for e-learning.”

Statements like this currently feature on learning solutions and technology industry websites around the world. In this week’s issue of Caveat Emptor we explore the mystery surrounding this hyperbolic advertising claim.

You might be tempted to accept that statement at face value when you see the results of this Google search. Surely these ‘facts’ about learning retention must be correct, given the large number of virtually identical listings revealed here? However there are a number of things about this that aroused our curiosity.

More lists of lists!

As you can see from Arad’s footnote above, the source cited for this is a list prepared by Christopher Pappas for elearningindustry.com called ‘Top 10 e-Learning Statistics for 2014 You Need To Know.’ The statement below ranks at number 8 in that list:

There are a couple of points worth noting here.

Firstly, Arad saw fit to switch the words ‘Virtual Training’ for the word ‘e-Learning’ used by Pappas when she reproduced the claim in her own post in 2016. It is still unclear why that was.

Secondly, Pappas refers to a ‘recent study conducted by the Research Institute of America’ but does not provide any further information about this. The link highlighted in blue leads to an unrelated article by Matthew Guyan entitled: ‘5 Ways To Reduce Cognitive Load In eLearning’. There is no mention of the ‘Research Institute of America’ in that article. So that proved a dead-end.

Those that read Issue 1 of Caveat Emptor may recall that the name Christopher Pappas cropped up as part of our investigation into ill-founded claims about the level of productivity generated by investments in e-Learning. In that instance our enquiries led us to the current version of a very similar list: ‘Top 20 eLearning Statistics For 2019 You Need To Know’.

As we reported last week, the 2019 list appeared to have been used as a source for many virtually identical but ill-founded marketing claims about productivity. This led us to wonder if a similar proliferation of claims about retention arose as a result of the earlier list compiled in 2014?

Reassured that we were seeking a ‘recent study conducted by the Research Institute of America’ our researchers set out to track the organisation down. This quest took far longer than we ever expected!

Seeking the Research Institute of America!

After much searching and some false trails we established that the Research Institute of America Inc. was a corporate-oriented, economics consultancy with a tax emphasis, based in Fifth Avenue, New York. In the 1980’s it was publishing ‘State and Local Taxes’ (comparison charts), ‘What you should know about your social security now’ (RIA Employee Handbook); The RIA complete analysis of the Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act of ’82; and other exciting titles.

By 1989 the RIA had become a US legal and tax publisher of some scale. In that year RIA was acquired by Thomson Corporation to augment it’s growing array of financial and tax information services businesses. Research Institute of America (RIA) ultimately became a division of Thomson Tax & Accounting.

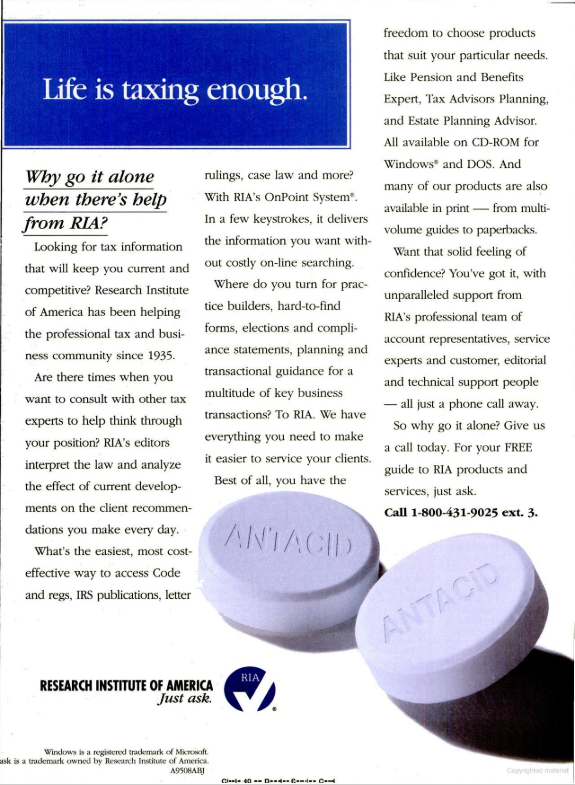

The RIA OnPoint System

In the late 1990’s the RIA announced the release of their OnPoint System, a new CD-ROM based program designed to assist those with an interest in tax information. A number of versions of OnPoint were produced. These were specialist products marketed through full page advertisements in magazines for accountancy and tax professionals. Here is an example from the ABA Journal issue of November 1995.

Users needed training to use the RIA OnPoint System so Student Versions of the CD-ROM were produced. These were abbreviated versions of the complete RIA OnPoint System computerized tax research database, designed to teach the user how to conduct tax research utilizing the database. For example, the RIA Onpoint System 4 Student Version Multimedia CD-ROM was issued on July 21, 2000.

WR Hambrecht & Co

As you can see from the information outlined above, the Research Institute of America was not an independent research institution that published academic peer-reviewed studies on learning effectiveness. On the contrary, they were a commercially motivated business forming part of Thomson Corporation. Moreover the organisation had a beneficial interest in selling computer based training and more latterly e-learning, for tax professionals. Their specialism was tax – not educational research.

Today the RIA brand lingers on at Thomson Reuters, Tax & Accounting but the Research Institute of America organisation itself disappeared decades ago. This is why it proved so hard to investigate this story via the Internet!

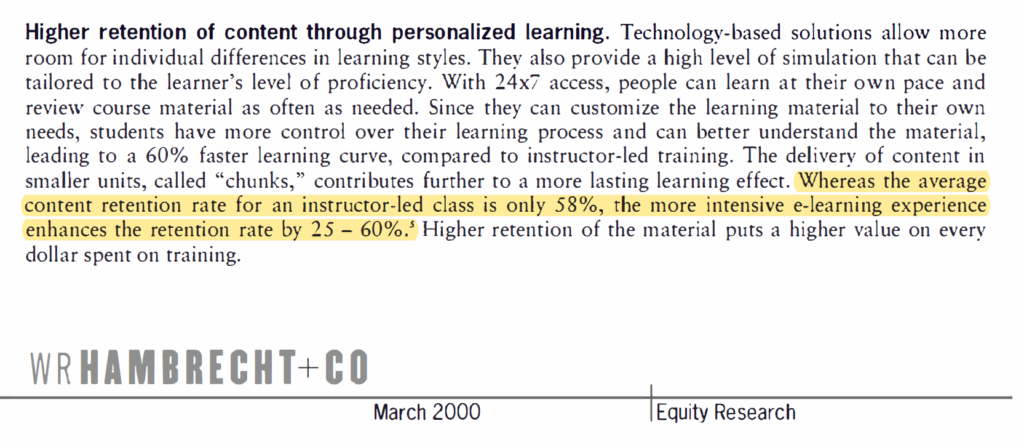

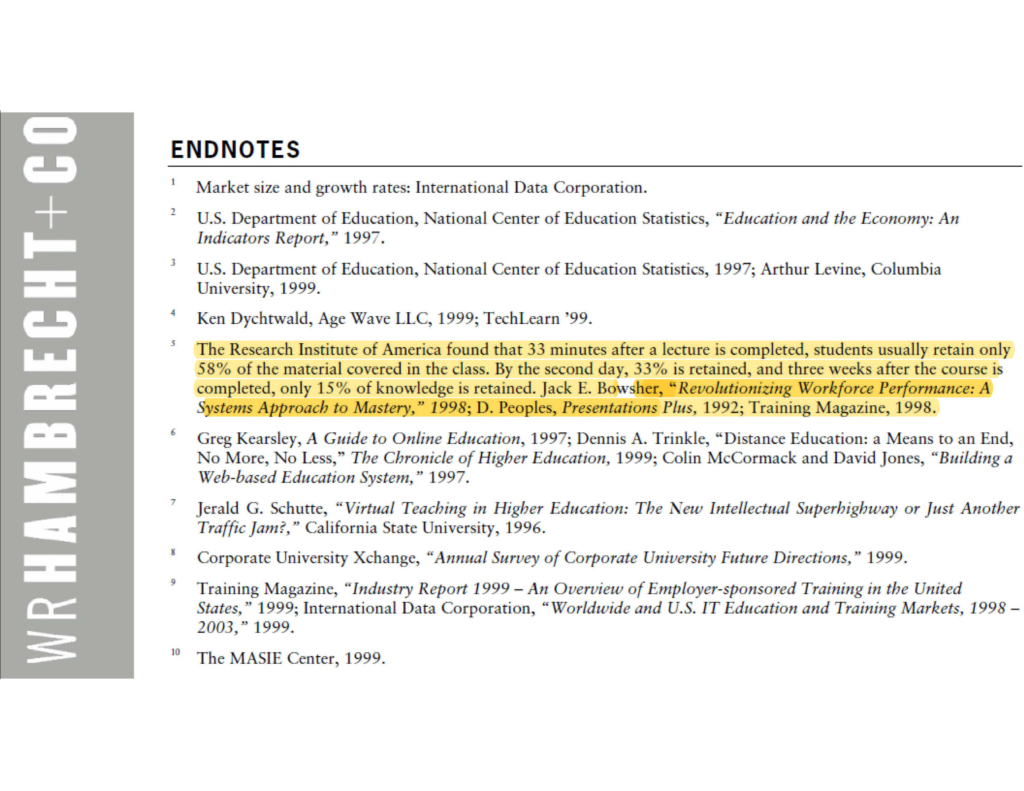

After a lot of work our researchers finally tracked down a report published by WR Hambrecht & Co in March 2000 entitled ‘Corporate e-Learning – exploring a new frontier‘. The following paragraph on page 6 finally allowed us to place a timeline on the claims associated with the RIA:

Given the date of publication for this report (March 2000) the source information for the highlighted text was probably gathered in the late 1990’s. Footnote 5 below explains where that information actually came from:

The ‘Endnotes’ are annoyingly vague. However this document was not a peer reviewed academic research study. It was simply a white paper written by a group of investment analysts who arguably had an axe to grind in promoting the benefits of e-Learning in the year 2000!

WR Hambrecht & Co made a market in the securities of DigitalThink, Inc. (DTHK), having underwritten of a public offering of securities of DigitalThink, Inc. within the previous three years. WR Hambrecht & Co also held private equity investments in Ninth House Network and Pensare, Inc. All three e-Learning vendors featured prominently in their report.

The forgetting curve?

The WR Hambrecht & Co ‘Endnotes’ above suggest the RIA stated the following information at some point in the 1990’s:

- That 33 minutes after a lecture is completed, students usually retain only 58% of the material covered in the class

- That by the second day, 33% is retained

- That three weeks after the course is completed, only 15% of knowledge is retained.

Many will recognise this as a bastardisation of the ‘Forgetting Curve’, which Hermann Ebbinghaus proposed after he ran a limited, incomplete study on himself from 1880 to 1885. He taught himself nonsense syllables and then tested himself after the initial exposure, recorded how many he remembered, reviewed them again and then repeated the process. The RIA may have done something similar or were simply citing results from another researcher. However it is not scientifically justifiable to draw broader conclusions about rates of forgetting from these kinds of results. As Will Thalheimer eloquently explains in his excellent white paper, everyone forgets things at widely differing rates.

It is unclear why the RIA were taking an interest in this particular subject. It is possible that the RIA was publicly promoting the benefits of self-paced learning as embodied by their Onpoint System 4 Student Version Multimedia CD-ROM in 2000 or shortly prior to that. That would certainly explain why a financial information business was advancing educational effectiveness claims. Given the role of WR Hambrecht & Co within the investment sector it is not unlikely that the two organisations were known to each other.

WR Hambrecht & Co do not quote the RIA as their source for the claim that e-Learning results in superior levels of retention. Confusingly, they reference a book by Jack E. Bowsher, called ‘Revolutionizing Workforce Performance: A Systems Approach to Mastery,’ published in 1998, a publication by D. Peoples called Presentations Plus published in 1992 and finally ‘Training Magazine, 1998′.

It remains unclear what mix of information from these varied 1990’s sources led to the authors to make their statement on page 6. However we have no doubt those sources could be tracked down if necessary.

One or more e-Learning vendors later extracted the wording from Page 6 of the WR Hambrecht & Co paper and simply credited the entire finding to the impressively (but misleadingly) titled Research Institute of America. The legend was born!

The Smoking Gun

There was little point progressing our enquiries back beyond the year 2000. The impression given to prospective buyers when e-learning vendors cite this statistic today is clearly misleading:

- The the study is not ‘recent’ – it is at least 20 years old and predates e-Learning as we know it today.

- The claim was the work of investment analysts gathered from multiple sources from the 1990’s rather than a direct finding from any single research study.

- The organisation cited (the RIA) is not an academic organisation publishing peer-reviewed research but a vendor of technology based training and financial information.

- Most importantly, this hyperbolic claim is unsupported by any of the well-documented peer-reviewed academic studies carried out since 2000!

We therefore encourage vendors to withdraw this claim immediately and not to repeat it.

Our findings from this investigation parallel our findings from last week. In both instances an apparently reputable source is being incorrectly cited for information that prospective buyers cannot rely on. This brings the provenance of many similar advertising claims into question.

In next week’s issue of Caveat Emptor we look at the broader issue of bogus learning effectiveness claims, how to spot them and what to do about it when you do!

Caveat emptor!

Let the buyer beware

Headlines on vendor sites across the web are currently screaming: “Every dollar invested in eLearning results in $30 of increased productivity!” However a Learning Accelerators investigation reveals absolutely no evidence that these claims can be substantiated.

The precise wording varies slightly from vendor to vendor, but as in the examples shown here the usual formula runs: “According to a study conducted by IBM, a company gains $30 worth of productivity for every $1 spent on online learning.”

You can click on the images below to see them in their original locations on vendor sites.

"No-one ever got fired for buying IBM"

“Nobody gets fired for buying IBM” is a phrase that anyone working in technology has come across over the last thirty years. Prospective buyers may well find it reassuring to hear that a technical solution has been subjected to a study by Big Blue.

It seems pretty unlikely that any responsible vendor would repeat this investment advice on their website, in proposals and white papers without doing some basic due diligence to check the information was actually true!

Sceptics might choose to run a Google search, finding these results which look consistently reassuring! After all, there are page after page of items published by different vendors – all repeating exactly the same information.

However someone with a suspicious frame of mind might ask themselves “Why have none of these suppliers published a citation or link to the actual source “IBM Study” in question?”

That does seem odd. If the full study findings were so definitive, then surely vendors would be keen to put the full text in front of prospective buyers?

Time for some critical thinking?

Learning Accelerators commenced investigations because the claim seemed “too good to be true”. The investment return claim raised many intriguing questions, including

- How could a genuine research study reach a definitive conclusion like this one without stating some qualification or disclaimer?

- How likely was it that that any genuine field study would reliably result in a metric of exactly 1:30?

- The ‘company’ might have gained productivity but relative to what baseline?

- Compared to doing nothing?

- Compared to classroom training?

Stripped of context we concluded the statistic was essentially meaningless. We had to know more!

Lists of lists...

It quickly became evident why this investment return claim is proliferating so widely across the web. Vendor marketeers appear to be reproducing items from lists of ‘e-Learning statistics’. For example the the investment advice above ranks at number 7 in a list of “Top 20 eLearning Statistics For 2019” compiled and published by Christopher Pappas of eLearning Industry in September 2019.

False trails

Some sources provided tantalising snippets of information about this mysterious study. For example on 7th April 2016 Karla Gutierrez of SHIFT e-Learning published an article entitled: ‘Facts and Stats That Reveal The Power Of eLearning’, alongside the infographic above.

Gutierrez even claims that the research finding on productivity gains appears in this 16 page IBM paper published in 2014 entitled ‘The Value of Training’ .

Sadly however, Learning Accelerators found no reference to such a finding in this particular IBM paper. The trail went completely cold for a while.

The Smoking Gun...

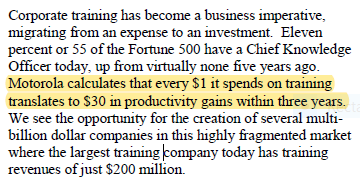

After a much searching Learning Accelerators traced the source of all the fuss to a similarly titled IBM White Paper entitled “The value of training – and the high cost of doing nothing” authored way back in 2008. Disappointingly all the grandiose claims boiled down to a mere handful of words on page three:

Footnote 9 to the report references a Merrill Lynch publication called “The Book of Knowledge” written in 1999, a period in which online learning was still climbing out from the evolutionary computer-based training ‘slime’.

The inescapable conclusion is that IBM were simply referencing a previous Merrill Lynch document, citing a Motorola “estimate” for productivity gains in 1999 arising from training (not e-learning) that had been achieved over an unspecified period of three years in the late 1990’s.

In the interests of completeness our investigators tracked down a copy of ‘The Book of Knowledge‘ to see what the reference seen by IBM researchers actually said. The only comment from Merrill Lynch on this matter is highlighted below as it appears on page three. This information is repeated again on page 134 but no further detail is provided.

We found numerous references to similar investment returns being claimed by Motorola in the late 1990’s. However all of these references state that the return on investment arose from training rather than specifically from investments in e-Learning. Since all this took place over 20 years ago and e-Learning did not exist in its current form at that time it is hard to see the relevance of this today.

Lessons learned

We attribute no blame or fault to either IBM or Merrill Lynch in relation to the sequence of events we have uncovered. Other parties chose to represent the information they originally published in the particular way they did, without effective due diligence.

‘Caveat emptor’ is a a long-established legal principle. In latin this means quite literally ‘Let the buyer beware!’ This refers to the principle that the buyer alone is responsible for checking the quality and suitability of goods before a purchase is made.

The results of this particular investigation show that the provenance of a key item of public domain ROI data commonly offered to clients in vendor proposals and in support of client investment business case development is false. We believe other items of ‘research data’ commonly quoted are similarly suspect.

We therefore recommend clients apply the ‘caveat emptor’ principle to this and any similar claims made without an attribution to the source.

In this case no ‘Investment Disclaimer’ appears to have been applied and the information provided to many buyers of eLearning products and services appears to be demonstrably incorrect.

Which raises the interesting question- if a vendor proposal for eLearning products or services was originally accepted on the basis of faulty investment advice and the client is later disappointed by the low productivity return – does any potential financial liability arise?

Discuss!

Learning Experience Designer role tops poll!

PRESS RELEASE

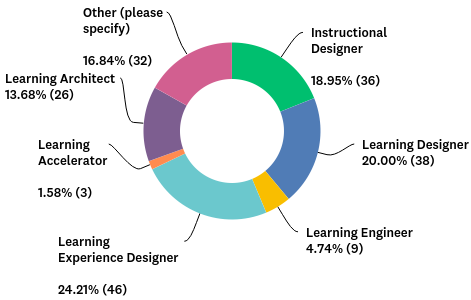

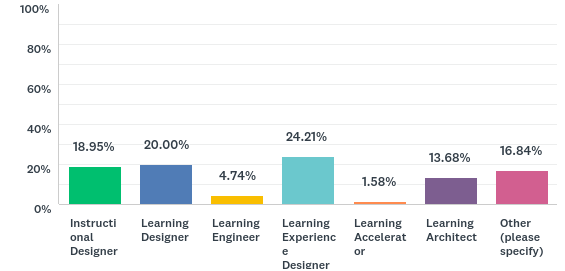

A global poll of learning professionals has revealed that the role title ‘Learning Experience Designer’ (LXD) is more popular than alternatives such as Instructional Designer, Learning Designer, Learning Engineer, Learning Architect.

LONDON, ENGLAND, UNITED KINGDOM, June 12th 2019

The results of an on-line survey seeking the role title most preferred by most learning professionals was announced at the CIPD ‘Festival of Work Conference and Exhibition today.

The poll was prompted by a light-hearted on-line debate between internationally respected learning evaluation expert Dr Will Thalheimer of Work-Learning Research and Adrian Snook of Learning Accelerators. Snook concluded that the best way to settle their debate was to “let the people decide!” via a speedy online poll.

The key question asked by Learning Accelerators in their poll was kindly suggested by Dr Thalheimer:

In total, 190 learning professionals responded to the short informal poll, representing opinions from a total of 25 different countries around the globe. Participants responded from: Australia, Canada, Denmark, Egypt, Estonia, France, Germany, India, Ireland, Israel, Malaysia, Netherlands, New Zealand, Philippines, Poland, Portugal, Puerto Rico, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, South Africa, Spain, Switzerland, Trinidad & Tobago, the United Kingdom and United States.

Snook commented: “Given the current excitement about ‘learner experience’ and the aggressive promotion of Learning Experience Platforms (LXPs) around the world, the popularity of the role title Learning Experience Designer is unsurprising.”

Blue Eskimo are specialist recruiters in the UK Learning arena. On seeing the survey results, Director Nick Jones was equally unsurprised.

Snook added “It’s surprising how evenly-divided global opinion turned out to be, with ‘Learning Experience Designer’ ranked first, just four percent ahead of the role title Learning Designer!”

The graph below highlights how closely ranked the results for Q1 were, with Instructional Designer, Learning Designer and Learning Experience Designer all competing for the top slot.

In addition to the standard options offered within the poll, respondents had the option of selecting their own preferred options. A diverse range of role titles were suggested, with the two top-ranking options being:

- Performance Consultant

- Performance enhancement champion/Performance enhancer.

On reviewing the poll results Dr Thalheimer commented:

About Learning Accelerators

Learning Accelerators draws on nearly thirty years of practical and commercial experience gained specifying, planning, buying designing and developing custom learning solutions for major national and international clients operating in both the private and public sector. Services on offer include; performance consulting, job and task analysis, learning needs analysis, learning options analysis, fidelity analysis, solution specification, support with supplier sourcing and selection, contracting, learning design, development and evaluation.

If you would like more information about this story, please contact Adrian Snook via our contact form.

Why we are all Learning Accelerators!

Will Thalheimer enjoys my deep respect because he is very rarely wrong. This is why I have been following his recent debate about selecting a new job title for learning professionals with special interest!

Will’s Heated Debate!

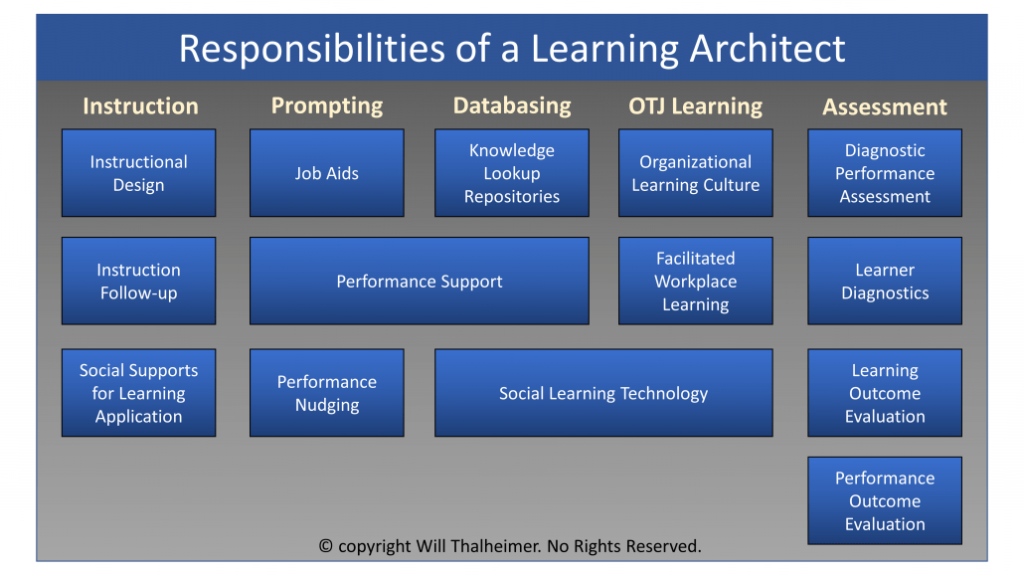

Will’s engaging and funny exploration of this subject has considered all the leading contenders for our new job title including: Instructional Designer, Learning Designer, Learning Engineer, Learning Experience Designer and finally, Learning Architect. And after weighing all these options he has now officially declared our new job title to be: Learning Architects. See: https://lnkd.in/e2ika8J

What do ‘Learning Architects’ do?

To be clear, Will is not simply saying that all the ‘artistes’ formerly known as learning or instructional designers will henceforth be Learning Architects.

Here is Will’s excellent breakdown of the very broad scope of work falling under his grand new job title:

credit: www.worklearning.com

Given the global esteem in which Will is held, no-one seems inclined to protest much about this, save for those concerned about the potential legal implications of using the word ‘Architect’.

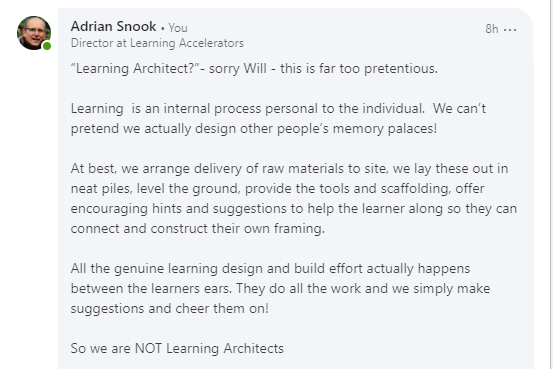

Why we are not ‘Learning Architects’

After watching Will’s debate for a couple of weeks, it is becoming clear that the die is being cast. We are all going to become Learning Architects unless I intervene to point out some significant issues with this plan!

So I contacted Will last night to lodge this protest via LinkedIn.

In essence my LI post represents the Second Guiding Principle of Accelerated Learning, which is that Learning is creation, not consumption. In other words, knowledge is not something a learner simply accepts like an architects client, but something that they themselves need to internally frame and construct. Learning only occurs when someone integrates new knowledge, skills or behaviour into their own pre-existing structures of understanding. Which is why I said:

In truth learning professionals do not really ‘create’, ‘design’, or ‘develop’ learning itself. This notion is a useful career fiction we all live with.

The role of the learning professional is to enable, facilitate and accelerate the work of learners as they do their own creative internal ‘design and build’. The title ‘Learning Architect’ would therefore be an grandiose affectation that does not reflect these realities.

Why we are all Learning Accelerators

So – if all learning professionals are not Learning Architects, then what are we?

Before formal learning was devised all ‘learning experiences’ were accidental, taking place at the snail’s pace of daily life. Children got lost in the woods at random and found that nettles sting the hard way. If they were lucky they found their way home again afterwards, having learned valuable lessons in local geography and botany.

Formal education and training artificially accelerates the slow and unpredictable pace of learner experience. Rather than leaving things to chance we create structured programmes of activities and thinking exercises. We offer useful models, tools, and resources, provide a safe space and scaffolding so our learners can work safely and with confidence. Whilst they are working to build their adapted model of the world we offer them advice and encouragement to prevent them becoming disheartened.

Modern learning professionals are able to draw on vast array of powerful resources and technologies. We pack rich, engaging activities tightly together, compressing experiences to support the learner in internalising new attitudes, knowledge and skills in hours, days, weeks or months rather than years or decades.

So all all learning professionals are therefore truly worthy of the title Learning Accelerator.

You Decide!

The mythical 10%…

-

A 1478 drawing by Theodoros Pelecanos of an alchemical tract attributed to Synesius. (Public Domain)

“Some studies have shown that only 10% of corporate training is effective“

Professor Michael Beer – Forbes, July 25, 2016

I have read many versions of the comment above, written various ways, over the last 30 years. Over the weekend I intervened in a LinkedIn discussion thread, headed with the quote above, which has so far attracted 47 ‘likes’ and 22 comments.

The thread arose from a re-post of this Forbes Article, under the headline: ‘Companies Waste Billions Of Dollars On Ineffective Corporate Training‘. The journalist who authored this piece and everyone involved in the LinkedIn discussion prior to my intervention appeared perfectly happy to accept Professor Beer’s hazy assertion that 90% of corporate training was ineffective.

This is puzzling, given that so many commentators worked in learning related roles. Surely the statement should have prompted some questions? Is it really likely that:

- Multiple genuinely evidence-based, peer-reviewed studies would produce a result that rounds to exactly 10%?

- Rational employers would have continued to fund learning related initiatives, year-on-year for this paltry return on investment?

I am puzzled by the persistence of this myth, which has appeared on the web, in business publications like Forbes, in training magazines (Chief Learning Officer, The Low-Hanging Fruit is Tasty, March 2006 Issue), books (The Learning Alliance by Robert Brinkerhoff and Stephen Gill), and even research papers (Baldwin & Ford, 1988).

If you trace your way back through these sources you soon discover that they all track back to a single rhetorical question posed in an article by David L Georgenson way back in 1982. On page 75 he asks:

“ How many times have you heard training directors say: ‘I…would estimate that only 10% of content which is presented in the classroom is reflected in behavioral change on the job’ ”

Georgenson, 1982

There are several key points to be made here:

- This is a question, rather than a statement of fact

- The 10% phrase is inside quotation marks, representing speech you might have heard

- The question was a rhetorical device to grab attention

- The question relates to content “presented in the classroom”

- No supporting studies or research whatever were cited in Georgenson’s paper.

It should be stressed that David L Georgenson was a product development manager for Xerox Learning Systems and not a researcher carrying out any kind of evidenced based, peer reviewed study.

Sadly many other researchers subsequently extracted Georgenson’s question and then elevated this to a statement of fact that not only applies to all forms of classroom learning, but to all investments made in learning!

This has resulted in many misleading statements, citing Georgenson as a source:

“It is estimated that while American industries annually spend up to $100 billion on training and development, not more than 10% of these expenditures actually result in transfer to the job”

(Baldwin & Ford, 1988, p. 63).

“Georgenson (1981) [sic] estimated that not more than 10% of the $100 billion spent by industry actually made a difference to what happens in the workplace!”

(Dickson & Bamford, 1995, p. 91)

In turn, the researchers that quoted Georgenson, were quoted by fresh researchers, pundits and salesman. Over time the legend grew.

Once the “10% myth” reached the Internet and this escaped into cyberspace it took on a life all of its own. It now pops up every few years to surprise a fresh generation of learning professionals.

There are specific reasons why spurious claims are sometimes repeated with more certainty and passion than the facts would support. Like the alchemists of old, some salesmen of today are seeking to convert dross into gold. If what you have is evidently broken – then you clearly need whatever they are selling.

Ironically – when Georgenson first posed his provocative question in 1982 most people would have answered him by saying “No – I have never heard any ‘training director’ say such a bizarre thing.”

However today, it is quite likely that you have – as a direct result of the myth that has grown up around his modest work.

Like the mythical great worm Ourobouros pictured above, the “10% legend” has now become self-sustaining, feeding on itself in the hidden places of the world for nearly forty years.

As learning professionals we all have a duty to avoid perpetuating this misinformation , especially in full view of the public and other members of the C-Suite.

So if the 10% myth pops up at an event or in a thread you participate in – please set the record straight!

For the early audit trail on this persistent and damaging myth please read this excellent paper by Robert Fitzpatrick.

Unpacking the Experience API

I recently put together a brief explainer for those unfamiliar with the concept of API’s in general and the xAPI in particular, prompted by a great question from Sam Rogers. I thought it might be helpful to share this here.

API simply stands for Application Programming Interface, a software intermediary layer that allows two applications to talk to each other. Each time you use the mobile app for LinkedIn, send an instant message, or check a stock price on your phone, you’re using an API.

When a company offers an API, this simply means they’ve built a set of dedicated web-links (URLs) that return pure data responses . This pure data can be used by another application for a range of purposes.

In 2010, Advanced Distributed Learning (ADL), the governing body for a much older e-Learning standard called SCORM, put out a call for a contractor to write a next-generation e-learning standard. Their goal was to provide a flexible way of recording learning-related activity taking place using a range of devices outside the restrictions of standard learning management systems, which primarily track progress through formalised learning activities.

Rustici Software was awarded the work, which began under the code name Tin Can. By August of 2012, version .95 of the Tin Can API was finalised. In April 2013 ADL coined the official name for the Tin Can API: the Experience API, or xAPI.

The specification for the Experience API (xAPI) achieved ADL’s ambitions and this now allows learning related content and learning systems to speak to each other, recording and tracking types of learning related activity not tracked in a conventional Learning Management System (LMS’s).

For example you could track data arising from micro-behaviours and conditions such as:

- Reading an article

- Watching a training video, stopping and starting it

- Training data from a simulation

- Performance in a mobile app

- Chatting with a mentor

- Physiological measures, such as heart-rate data

- Micro-interactions with e-learning content

- Team performance in a multi-player serious game

- Quiz scores and answer history by question

- Real-world performance in an operational context

xAPI helps us answer interesting questions like:

- What learning or work related resources are people accessing?

- What answers are people getting wrong?

- What time of day or night are people accessing learning?

The launch of the xAPI specification in turn spawned a plethora of what are now termed Learning Experience Platforms (LxP’s) Not only that – traditional LMS vendors have responded defensively to bolt Learning Experience-like solutions onto their own offerings.

As Josh Bersin points out in this useful article: “People no longer search course catalogs for ‘courses’ the way the used to, and we need a way to train and learn ‘in the flow of work.'”

However, measuring learning activity is not the same thing as measuring learning itself, nor the measurement of learning impact on business outcomes.

In medical terms most interactions tracked via the xAPI are symptoms suggesting that learning may well be taking place.

By contrast the LMS monitors the pulse and blood pressure in the pulmonary system as formal learning experiences are pumped around the cells in the corporate body.

However we still need to measure the resulting shifts in performance as the organisation competes with other corporate athletes for new opportunities and markets.

Shifts in behaviour may be indicated by current LXP’s but the hard data analytics that prove the desired business impact has occurred currently need to come from other enterprise systems. The next step is to extend xAPI into those enterprise systems so these are more closely integrated into the flow of work.

To review the full technical spec for xAPI please click here.