Let the buyer beware

Headlines on vendor sites across the web are currently screaming: “Every dollar invested in eLearning results in $30 of increased productivity!” However a Learning Accelerators investigation reveals absolutely no evidence that these claims can be substantiated.

The precise wording varies slightly from vendor to vendor, but as in the examples shown here the usual formula runs: “According to a study conducted by IBM, a company gains $30 worth of productivity for every $1 spent on online learning.”

You can click on the images below to see them in their original locations on vendor sites.

"No-one ever got fired for buying IBM"

“Nobody gets fired for buying IBM” is a phrase that anyone working in technology has come across over the last thirty years. Prospective buyers may well find it reassuring to hear that a technical solution has been subjected to a study by Big Blue.

It seems pretty unlikely that any responsible vendor would repeat this investment advice on their website, in proposals and white papers without doing some basic due diligence to check the information was actually true!

Sceptics might choose to run a Google search, finding these results which look consistently reassuring! After all, there are page after page of items published by different vendors – all repeating exactly the same information.

However someone with a suspicious frame of mind might ask themselves “Why have none of these suppliers published a citation or link to the actual source “IBM Study” in question?”

That does seem odd. If the full study findings were so definitive, then surely vendors would be keen to put the full text in front of prospective buyers?

Time for some critical thinking?

Learning Accelerators commenced investigations because the claim seemed “too good to be true”. The investment return claim raised many intriguing questions, including

- How could a genuine research study reach a definitive conclusion like this one without stating some qualification or disclaimer?

- How likely was it that that any genuine field study would reliably result in a metric of exactly 1:30?

- The ‘company’ might have gained productivity but relative to what baseline?

- Compared to doing nothing?

- Compared to classroom training?

Stripped of context we concluded the statistic was essentially meaningless. We had to know more!

Lists of lists...

It quickly became evident why this investment return claim is proliferating so widely across the web. Vendor marketeers appear to be reproducing items from lists of ‘e-Learning statistics’. For example the the investment advice above ranks at number 7 in a list of “Top 20 eLearning Statistics For 2019” compiled and published by Christopher Pappas of eLearning Industry in September 2019.

False trails

Some sources provided tantalising snippets of information about this mysterious study. For example on 7th April 2016 Karla Gutierrez of SHIFT e-Learning published an article entitled: ‘Facts and Stats That Reveal The Power Of eLearning’, alongside the infographic above.

Gutierrez even claims that the research finding on productivity gains appears in this 16 page IBM paper published in 2014 entitled ‘The Value of Training’ .

Sadly however, Learning Accelerators found no reference to such a finding in this particular IBM paper. The trail went completely cold for a while.

The Smoking Gun...

After a much searching Learning Accelerators traced the source of all the fuss to a similarly titled IBM White Paper entitled “The value of training – and the high cost of doing nothing” authored way back in 2008. Disappointingly all the grandiose claims boiled down to a mere handful of words on page three:

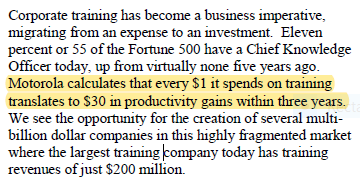

Footnote 9 to the report references a Merrill Lynch publication called “The Book of Knowledge” written in 1999, a period in which online learning was still climbing out from the evolutionary computer-based training ‘slime’.

The inescapable conclusion is that IBM were simply referencing a previous Merrill Lynch document, citing a Motorola “estimate” for productivity gains in 1999 arising from training (not e-learning) that had been achieved over an unspecified period of three years in the late 1990’s.

In the interests of completeness our investigators tracked down a copy of ‘The Book of Knowledge‘ to see what the reference seen by IBM researchers actually said. The only comment from Merrill Lynch on this matter is highlighted below as it appears on page three. This information is repeated again on page 134 but no further detail is provided.

We found numerous references to similar investment returns being claimed by Motorola in the late 1990’s. However all of these references state that the return on investment arose from training rather than specifically from investments in e-Learning. Since all this took place over 20 years ago and e-Learning did not exist in its current form at that time it is hard to see the relevance of this today.

Lessons learned

We attribute no blame or fault to either IBM or Merrill Lynch in relation to the sequence of events we have uncovered. Other parties chose to represent the information they originally published in the particular way they did, without effective due diligence.

‘Caveat emptor’ is a a long-established legal principle. In latin this means quite literally ‘Let the buyer beware!’ This refers to the principle that the buyer alone is responsible for checking the quality and suitability of goods before a purchase is made.

The results of this particular investigation show that the provenance of a key item of public domain ROI data commonly offered to clients in vendor proposals and in support of client investment business case development is false. We believe other items of ‘research data’ commonly quoted are similarly suspect.

We therefore recommend clients apply the ‘caveat emptor’ principle to this and any similar claims made without an attribution to the source.

In this case no ‘Investment Disclaimer’ appears to have been applied and the information provided to many buyers of eLearning products and services appears to be demonstrably incorrect.

Which raises the interesting question- if a vendor proposal for eLearning products or services was originally accepted on the basis of faulty investment advice and the client is later disappointed by the low productivity return – does any potential financial liability arise?

Discuss!